When the 30-plus sled drivers, or mushers, as they are commonly called, and several hundred sled dogs set off at the start of the 53rd Iditarod on March 1, 2025, they face a trail of approximately 1,000 miles of rugged wilderness with the possibility of bone-chilling temperatures, raging blizzards, and serious threats from moose and other wildlife. The trail crosses an isolated landscape of tundra and forests, over hills and through mountain passes, across frozen rivers and over sea ice that, depending on the temperature, may or may not be safe to cross. It passes through small towns, villages, and native Athabaskan and Inuit settlements, serving as checkpoints where mushers and their teams can rest. If all goes well, a week or so later, one team will be the first to cross the finish line, the famous burled arch in Nome. But the race isn’t over until the last musher and their dogs cross the line or are otherwise accounted for. The Iditarod is not the only race of its type—the Yukon Quest, which runs from Fairbanks to Whitehorse, Canada, is another 1,000-mile annual dog sled race—but The Iditarod is Alaska’s best-known sporting event, even if most people don’t know its history or significance.

The race traditionally starts in Alaska’s largest city, Anchorage, which allows the teams to pass crowds of cheering fans, but it has a second official start the next day in the town of Willow, 70 miles north, where the teams take off on the snow-packed wilderness trail. Official events, however, start weeks before, says Shannon Noonan, director of marketing and communication for The Iditarod. “Leading up to the race, events, and ceremonies celebrate the history of sled dog transportation, often featuring stories of the original mushers and their dogs, emphasizing their importance in Alaska culture.” Honoring Alaska’s history is what The Iditarod is all about.

The historic connection

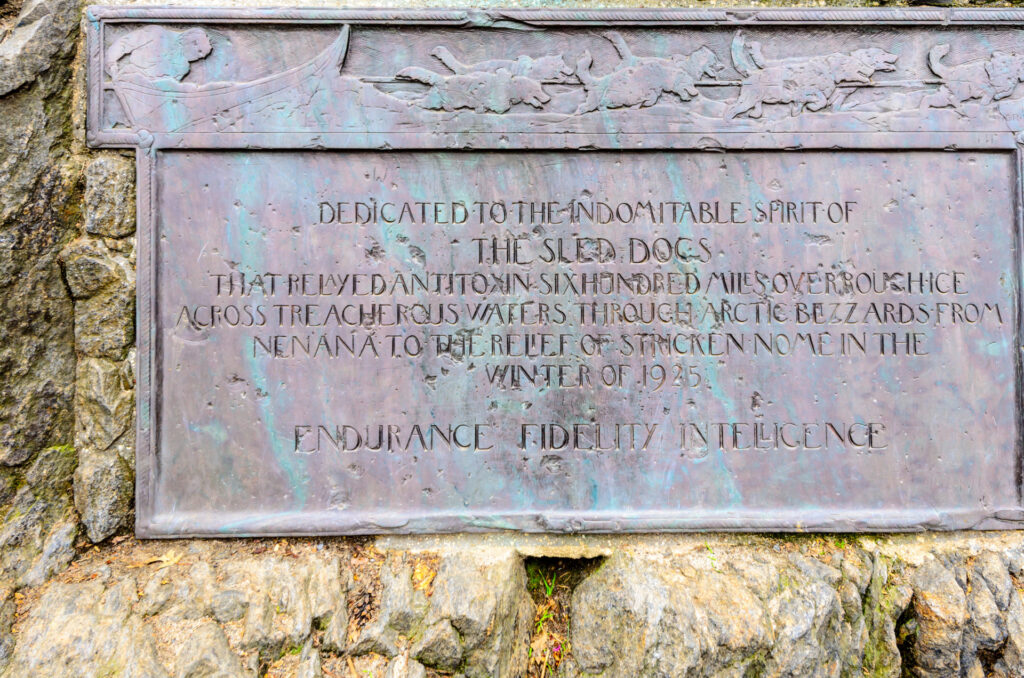

When most people in the Lower 48 think of The Iditarod or of sled dog racing, they probably think of the famous dog Balto and his role in the historic delivery of serum that saved the lives of hundreds of children in northwest Alaska during a Diphtheria epidemic in 1925. Balto was the lead dog in the last blizzard-filled leg of a nearly 700-mile serum run from Seward to Nome that involved more than 20 mushers and about 150 sled dogs in a Pony Express-type relay. The news coverage of the feat, thanks to the newly popular medium of radio, brought worldwide attention to Balto and his musher Gunnar Kaasen, sled dogs, and Alaska in general, which was still decades away from becoming a state. But the race and tradition of sled dogs are much more than that of one famous run. In fact, The Iditarod has as much to do with Alaska’s gold rush history as with the epidemic.

Dog Sleds as freight transport

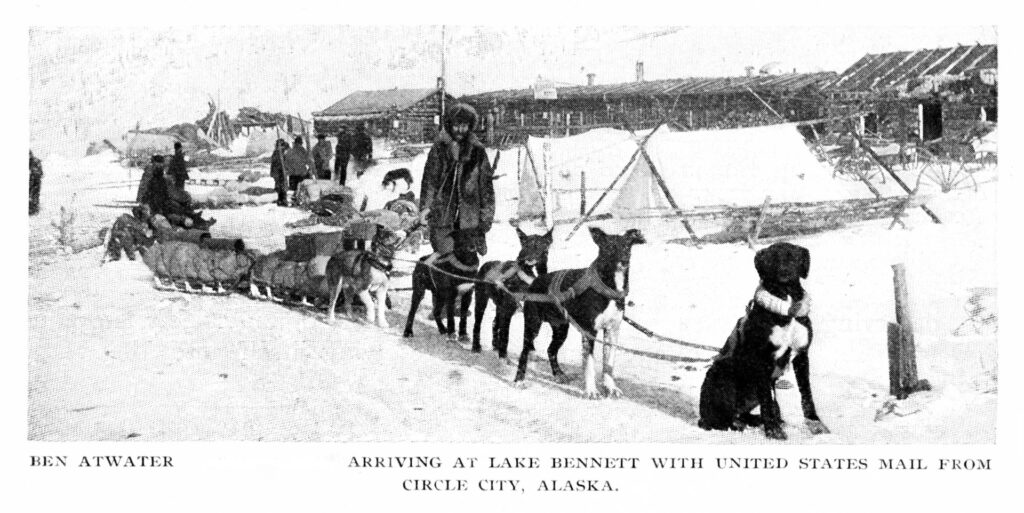

According to trail history at Iditarod.com, there were more than 30 serious gold rushes between 1880 and 1914, most of which drew eager prospectors to isolated areas of the Alaska territory. Many of the gold districts were served by steamboats in the summer months but were virtually inaccessible during the winter, which in Alaska usually means October through May. By 1910, the need for mail and freight service to these areas led to the construction of a winter trail from Seward to Nome. Dog sleds, used by Alaska natives for centuries, were the most practical means of transport because dogs, as opposed to horses or oxen, were able to run over ice and snow without breaking through and could be fed with wild game killed along the way. A typical freight hauler on this trail, which much of today’s Iditarod Trail follows, had a team of 20 or more dogs that could pull a sled weighing half a ton.

Even as airplanes became more common, dog sleds were used well into the 1930s, and even during WWII, mushers and their teams patrolled the vast winter wilderness in Alaska. At the time of the 1925 epidemic, the most experienced bush pilot wasn’t available, and the weather made flying nearly impossible, so sled dogs were called into service. According to Iditarod.com, the popularity of the snowmobile in the 1960s and ‘70s, not the airplane, resulted in the abandonment of dog teams across the state and, with that, the potential loss of a big part of Alaskan history.

In 1967, hoping to stem this loss and to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Alaska becoming a U.S. Territory, organizers began looking into the idea of a race along the old Iditarod Trail, and in 1973, the first official Iditarod, today known as ‘The Last Great Race on Earth,’ was run. “In that way, the route itself is a living tribute to those early pioneers and their sled dog teams,” Noonan says.

The early years

Although the first race followed an existing trail, it wasn’t as complete in the early years as it is today. In an article for AlaskaNewsSource.com, musher Joe May, champion of the 1980 race, recalled, “The race truly took place on a ‘broken trail,’ as mushers would often times clear a trail ahead of the dogs using snowshoes and other tools.” May noted mushers who ran the race in those years did it to test their endurance. “When I got to [the finish line], I didn’t think of myself as a winner, but rather a survivor. The prize money was little more than enough for a good party and plane fare home.”

In 1973, musher Dick Wilmarth and his team won the first race, completing the course in a little over 20 days. Over the decades, the race has gotten faster, and since the mid-1990s, the winner usually crosses the finish line in eight to 10 days, with the final musher making it in by day 15. The dramatic improvement in race times over the past 50 years is mostly due to two factors, according to that article: stronger dogs and improved gear, including a sled that offers the mushers more comfort on the grueling route.

Quoted in the article, four-time Iditarod champion Jeff King—who is credited with developing the first sit-down sled—says, “We couldn’t keep up with the dogs before that. There wasn’t a musher alive that could get through an eight-day race without having sat down a good share of the time the dogs were moving.” The sled King is credited with developing in 2004, dubbed the “Iditarod Barcalounger,” gives mushers the option of sitting or standing while racing.

While the early participants raced to test their own fortitude, today’s mushers race for the glory, a trophy, and cash prizes. The field of 29 finishers in the 2024 race shared a purse of over a half million dollars. According to race officials, six-time winner Dallas Seavy claimed $55,900; runner-up Matt Hall took home $47,250; and third-place finisher Jessie Holmes won $43,400. The top 20 finishers receive decreasing amounts, with the 20th place finisher taking home $12,400. The remaining mushers all received $2,000 each for their efforts.

With his win in 2024, Seavey became the most celebrated musher in the history of the race. In 2012, at age 25, he was the youngest musher to win. He has run and completed The Iditarod 13 times, finishing in the top 10 11 times.

Other significant winners include Libby Riddles, who, in 1985, was the first woman to win the race, and Susan Butcher, who won four times over five years (finishing second the other year) and is among the most recognized mushers, male or female.

It’s really all about the dogs

Sled dogs that run competitive races are elite athletes and have gotten stronger over the decades with improved care and better food. Today, The Iditarod makes significant efforts to prioritize the health and welfare of the sled dogs, Noonan says. “This includes strict veterinary protocols, on-trail veterinary checks, and educational campaigns about responsible dog care. These initiatives ensure that the dogs are healthy and well-treated, which is crucial for the integrity of the race and the sport.” She notes the race integrates and showcases Native Alaskan cultures, many of whom have a long history of using sled dogs for transportation, while it also reflects the historical bond between mushers and their dogs and honors the legacy of the sled dogs that were essential to the freight delivery system.

Over the past two decades, the organization has been involved in veterinary research studies at numerous state universities across the U.S. “Information from these studies, focusing on cardiovascular, muscular, skeletal, and gastrointestinal health, and overall nutrition of sled dogs, have benefited pets around the world,” according to Iditarod.com.

Today’s route varies on even and odd years to involve different terrain and different communities, with 26 or 27 checkpoints along the way. Mushers are required to stop three times during the race, twice for eight hours each and once for 24 hours. Mushers also use the checkpoints for resupplying, relying on a team of volunteer pilots known as the Iditarod Air Force, who fly into the various checkpoints to deliver drop bags the mushers have filled with extra food and supplies for themselves and their dogs.

Having these villages as checkpoints also allows for more community involvement, Noonan says. “This is an important part of the race. Each community and native village on the trail participates in The Iditarod, celebrating their heritage and the role of sled dogs in their history. And veterinarians who are stationed in the communities to check the health of the dogs in the race also offer health care, checkups, and vaccinations to dogs in the communities.”

Before the race, the dogs are required to complete a full physical exam, including EKGs and full bloodwork, and during the race, well over 1,000 veterinary examinations take place to ensure that every dog is healthy and receiving the care it needs. According to an article at Iditarod.com, “Mushers work hard to keep their dogs healthy and happy. The dogs must have stamina and be mentally capable of making the run. Unlike a team sport such as basketball, there are no substitutions. The musher’s goal is to arrive in Nome with healthy and happy dogs. Without these four-legged athletes, there is no race.”

Race initiatives

Over the years, The Iditarod has developed several initiatives supporting the culture and history of the race, the state, and the sport.

“The race integrates and showcases Native Alaskan cultures, many of whom have a long history of using sled dogs for transportation,” Noonan says. “This connection reinforces the importance of traditional practices and stories in the modern context of the race. Initiatives that highlight the stories of Indigenous peoples and the historical significance of the Iditarod Trail help preserve this heritage and educate participants and spectators alike.” In 2023, the top three finishers were Alaska natives.

The Iditarod also encourages all the mushers, whether from the state or elsewhere, to learn about the history of the sport, “including the techniques and practices of past freight mushers,” she says. “This education fosters a deep appreciation for the skills and endurance required to navigate Alaska’s challenging terrain.”

Iditarod.com features a full section devoted to how The Iditarod can be used in the classroom. Educational programs teach the history of dog mushing and its significance in Alaskan life, ensuring that future generations understand and appreciate this aspect of their culture. The Iditarod EDU program also hosts the annual Trail Mail program that pays homage to the Iditarod Trail as an early mail route. Julie Westrich, one of the participating teachers, writes, “Trail Mail is required gear. Mushers carry a small cachet of letters in their sled the entire length of the Trail and present it in Nome to be postmarked and returned to the original sender. It is a great program from the Iditarod EDU that connects classes, the Iditarod, and the mushers around the world through mail.”

Another Iditarod initiative focuses on the environment with efforts to reduce waste at checkpoints, promote eco-friendly practices among participants, and raise awareness about the impact of climate change on the race and the Alaskan wilderness. Another is the Iditarod Insider, a subscription-based program that provides live coverage, behind-the-scenes content, and in-depth insights. “This humanizes the race and helps fans connect more deeply with the participants,” Noonan says. “The Insider platform often includes educational segments about dog care, training, and the history of The Iditarod, all of which promotes a better understanding of the sport and the responsibilities involved in dog mushing.”

Beyond The Iditarod

According to AlaskaTours.com, there are numerous qualifying races around the state and opportunities for people to try the sport. Local racing clubs and circuits also help keep the sport alive.

ADMA (Alaska Dog Mushers Association) is a sprint racing organization in Fairbanks where most people just compete for fun, says Andrea Bond, ADMA secretary. “Sprint is a different style of racing, with our competitors going from four to 30 miles per day at slower speeds, with race times cumulative from all days of the event. We have participants from Fairbanks, all over Alaska, Canada, the lower 48, and a few from other countries.”

The organization runs its 79th Open North American Championship this spring, says Shannon Erhart, vice president of ADMA. “Other forms of the race were before that, so really, we’re going on 100 years. Our race is considered the ‘cream of the crop’ in spring mushing.”

Raising and racing sled dogs is a sport that “runs in the family,” Erhart says. “Some of us have a family history, and some folks come to Alaska and want to get involved in the state sport, start with a smaller team, and get hooked. The same can be said for Juniors. (Junior teams are for kids ages three to 16). I know many juniors who wanted to mush, and their families got involved that way. It is a very family-friendly sport.”

It is not an inexpensive sport to participate in. “We usually budget $1,000 a year per dog, but that is probably underestimating now as prices have been steadily rising for high-quality feed and bedding, as well as veterinary care,” says Bond. “We have a mid-size kennel that fluctuates from 30 to 50 dogs. All three members of our family pitch in with chores and training, and we all race competitively. We use a heated trailer that also has a camper for us to stay in for some races. So yes, it can be a lot of specialized equipment and a different lifestyle. Our whole lives revolve around the dogs and puppies.