Lessons from the organizers of two of America’s most beloved 24-hour mountain bike races.

Roughly 20 years—and 30 pounds—ago, I participated in my first (and only) 24-hour mountain bike race. I was part of a five-person relay team of varying riding skills and abilities, ranging from intermediate to expert, though we had no delusions of actually winning. No, in terms of our goals, we were there to challenge ourselves and have fun—our team name was Beer is Beer, after all—and that’s just what we did. The event ran from Friday to Sunday, and we got there early on the first evening, set up our tents, wandered around the grounds, checked out the vendors, grabbed some swag, ogled other riders’ often much better bikes, grilled burgers, and drank a beer (or two) before bed. After breakfast on day two, we prepped our bikes, and once the race started at noon, we committed to the cycle of ride, eat, sleep, and repeat throughout the night until the race wrapped up at noon the next day.

In the end, I can’t recall where our team placed among the hundred or so other teams, but I remember that we completed 19 loops through the hilly, gnarly single-track terrain. In contrast, the top solo rider completed 20. And while the fact that our whole team did fewer laps than one (obviously elite) rider might be considered embarrassing by some, my lasting impression of the event is hardly one of defeat. Rather, it’s a sense of personal accomplishment and pride. As well, I remember the positive vibe and overall festive energy buzzing around the event. Today, 24-hour races are not as popular as they once were, taking a backseat to the more fashionable cyclocross or gravel bike riding, but they’re still well-loved among hardcore and fun-loving riders. And there are still a few 24-hour races going strong, with likely room in the country for more.

To understand what it takes to host a successful 24-hour mountain bike race, we spoke with Ryan Parnell, director of 24 Hours in the Canyon held in Palo Duro Canyon, south of Amarillo Tex., and Todd Sadow, founder of TMC Health 24 Hours in the Old Pueblo near Tucson, Ariz. While their business models differ—Canyon raises funds for cancer survivorship programs, while Old Pueblo is one of three events produced by Sadow’s company Epic Rides—both events have built deep connections with their communities by focusing on culture, quality, and an unforgettable rider experience. Here’s some of their podium-worthy advice.

On rationale

Every great event starts with a strong “why.” For Ryan Parnell, 24 Hours in the Canyon began in 2007 after a personal cancer scare. “It just sucked,” he says of the diagnosis and the stress of waiting for results from a biopsy. Thankfully, it wasn’t cancer after all, but Parnell and his wife wanted something positive to come out of the negative experience. “We felt like we needed to do something, and I had heard of someone who had put on a 24-hour event elsewhere… and thought, we love to ride bikes, why don’t we do a 24-hour event?”

What began as a third-party fundraising ride has since grown into an established nonprofit event under the Harrington Cancer and Health Foundation, where Parnell serves as director of operations and special programs. Today, the event raises around $400,000 annually to support cancer survivorship care—and has donated over $3.5 million in total since it began in 2007.

Parnell credits the longevity of his volunteer team as a core strength. “Our committee is made up of the most ragtag bunch of folks,” he says with a chuckle. “Everyone has a cancer connection. We have a good mix, all volunteers, and many of them have been with me for 10, 12, 15 years.” Most of them do not ride bikes, he adds, which works out well because it means there are people to help produce the event. “If you build it with everybody who rides bikes, then that’s what they’re going to do, ride your event and not work and volunteer to make the event happen,” Parnell says.

For Sadow, 24 Hours in the Old Pueblo emerged from a desire to bring back the fun, inclusive spirit of early mountain biking. In the late 1990s, 24-hour races were just emerging as a response to the increasingly competitive and intimidating landscape of mountain biking. “24-hour racing broke that barrier down,” Sadow says. “It really harbored a lot of camaraderie… and it made it fun for everyone that wanted to be a part of it.”

Founded in 2000, Old Pueblo was one of the first events produced by Epic Rides, an event production company that now runs three mountain biking events in Arizona. And while the company model is commercial, the spirit is community-driven. According to the Epic Rides website, “each of our events is more than just an event. It’s a celebration of the bicycle, the outdoors, and the individuals and organizations who make the mountain biking community the coolest group of people on the planet.” Indeed, Sadow says the organizers are now just stewards of a community at this point. “We produce the event,” he says, “but it’s all that happens within the framework of that event that makes it so special.”

On culture

Both races have thrived by staying true to their core communities. For Sadow, that means keeping the event welcoming and rider focused. “We try not to take things too seriously,” he said. “As a company, we’ve always focused on second through last place, because there’s way more of them.”

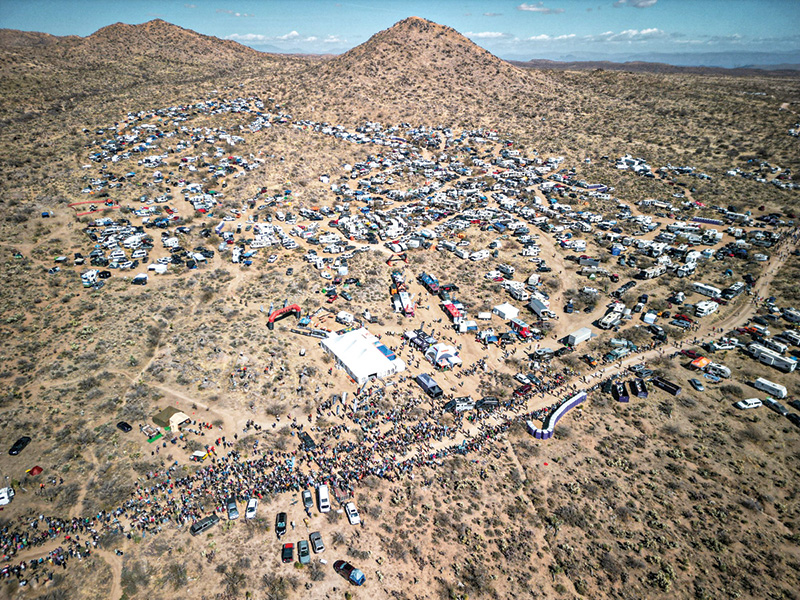

24 Hours in the Old Pueblo is now one of the most in-demand endurance mountain bike races in the U.S. “Registration opens on October 1 each year, and it fills up in about an hour with 2,000 registrations,” Sadow explains. “24 Hour Town, our venue, sees about 4,000 total people for the weekend living together.”

Sometimes described as the Burning Man of bike racing, the event is known for its inclusive, festival-like vibe. “It’s Burning Man with a healthy tilt,” Sadow says, elaborating on the experience. “I always say it’s a window into humanity redeeming itself because it’s this time where you can just be yourself. Everyone has the bike in common,” he says. “It’s a place where you can be, proudly, a mountain biker of all types. It doesn’t matter, beginner, expert, pro. Everyone’s there. You’ve got CEOs of major corporations on the same team as kids who are bike shop wrenches with grease under their nails, and they’re having the time of their lives together. They don’t think about the Monday to Friday, 9 to 5 grind.”

At 24 Hours in the Canyon, inclusive culture is equally important, as is participant satisfaction. Parnell strives to provide an experience that makes people want to come back the next year. “We want to make sure we give a good product that’s better than advertised, honestly, so that they get more bang for their buck and they feel like they need to come back year after year,” Parnell says. “I would much rather have 90 percent of my people come back year after year than have to go find 75 percent new participants.”

On logistics

Running a 24-hour race means anticipating—and adapting to—a huge number of moving parts. From course design to rider check-in to contingency plans for bad weather, both organizers emphasized the need for deep planning and operational flexibility.

To produce Old Pueblo, Sadow’s onsite team includes about 25 paid staff and 250 volunteers in the month leading up to and at the event. Essentially, they’re creating a whole town in the middle of the Sonoran Desert north of Tucson. “It is very complex, and the learning curve at times has really smacked me around. There have been some serious barriers and things to sort out,” he says, noting the importance of not cutting corners when it comes to respecting the landscape. “Every year we make a point to leave it better than we found it, and that’s what allows us to keep coming back,” Sadow says. “It’s a big part of mountain biking—being a good steward of the land.”

At 24 Hours in the Canyon, the core committee includes about 40 volunteers, plus 75 to 100 more on race weekend. “It’s quite an undertaking,” says Parnell, who handles about 90 percent of the planning leading up to the event, then lets his team take over during it. “We transform Palo Duro Canyon,” he says. “We have every single camp spot reserved a year in advance. There are people everywhere, but the cool thing is that all those people are on bikes.”

To streamline logistics, Parnell uses the OneCause fundraising platform for registration and fundraising and the guestlist app for on-site check-in. “I live in the OneCause database six months out of the year,” he says. “It is very customizable and user-friendly on the back end. I can’t recommend it enough.”

On accessibility

At Old Pueblo, the 17-mile hand-built desert loop caters to a wide range of skill levels. “The beginner can confidently complete the course. The pro can do it as fast as they can,” Sadow says. The event also limits solo racers to 200 and features relay team formats that allow more casual participation.

Sadow estimates: “Five per cent can actually win. 20 percent are racing. 60 percent are there to beat their previous fastest time or beat their teammates. The rest have no idea what they’ve gotten themselves into.”

24 Hours in the Canyon splits riders into competitive and non-competitive courses and offers several timed options. “A participant suggested once, ‘I just don’t want to do 24 hours, but I can ride for 12,’” Parnell says. “So, we start a group at midnight for a 12-hour and a group at 6 a.m. for a six-hour.” The key, he says, is to listen to your participants and make the event as accessible to as many people as possible.

On rider experience

Beyond the race itself, both events offer thoughtful extras that boost rider satisfaction and long-term loyalty. At Canyon, riders enjoy a Friday night spaghetti feast and a Saturday meal—both sponsored—as well as a VIP “Pre-Ride Party.”

Kids get in on the action, too. “We do a kids’ ride before the event starts, that’s free… They have a bib number just like mom and dad do,” Parnell says. “It’s important to engage those kids because guess what happens—they get older, and now they’re participating in your main event.”

Old Pueblo similarly offers music, community recognition toasts, and a lively weekend schedule. “Programming begins on Friday at noon,” Sadow says. “24 Hour Town is very lively.”

On the payoff

Organizing a 24-hour race isn’t easy. It requires vision, tenacity, and a deep connection to the people who show up year after year. But for both Parnell and Sadow, the rewards go far beyond the finish line.

“I remember saying, ‘Hey, if I’m still doing this in 10 years, please shoot me,’” Sadow says with a laugh. “Now, 25 years later, I feel like this is the greatest privilege in the whole world.”

Parnell agrees: “We’ve donated over $3.5 million to provide care and support for cancer survivors. It’s not just about the ride—it’s about what it makes possible.”

Whether your goal is to raise funds, build community, or simply get more people on bikes, the path forward is the same: build with purpose, stay flexible, and never underestimate the power of a great trail, a strong team, and a starry night ride.