A mild winter is a pleasant thought for many across the United States. Yet, a warmer winter isn’t so hot for others—particularly those who seek to partake in cold-weather sports like skiing and snowboarding each season. However, as data reveals, warmer winters are becoming more frequent.

According to Climate Central, December—the first month of the meteorological winter—has shown to be the fastest warming season in the U.S., with further analysis by Climate Central disclosing November temperatures are rising by as much as 2.1 F in many locations as well. In addition, even the “cold” days of winter are not as cold as they once were; approximately 84 percent of U.S. locations report at least seven more days above normal winter temperatures since 1970, with many cities across the country having warmed approximately 3.8 F between 1970 and 2022.

That, however, doesn’t mean there are no longer cold spells—just fewer of them. Data from Climate Central shows many locations across the U.S. have experienced fewer cold snaps in winter since 1970, with those cold snaps shrinking by six days on average. The organization also notes fewer nights with temperatures dipping into freezing temperatures, which have decreased by 13 nights as well.

“Essentially, anywhere you look, winter temperatures are climbing, and the science projects the trend to continue,” notes Peter Girard, director of communications for Climate Central.

An alarming trend

These statistics must be alarming for anyone involved in the winter sports industry, particularly snow-based sports, as they are potentially poised to take a dramatic hit. After all, as the National Environmental Education Foundation notes, snow-based sports contribute approximately $67 billion annually and support more than 900,000 jobs in the U.S. Climate Central even reports winter sports account for upwards of 150 million jobs. But on a positive note, as Girard shares, despite the data showing warming trends over the last five decades, it doesn’t necessarily mean snowfall will stop.

“In some places, snowfall trends aren’t necessarily expected to drop,” he says. “Of course, it needs to be cold enough for that precipitation to fall as snow. Broadly, as temperatures climb and our winters get warmer, many people expect there will just be less snow, but that isn’t the case everywhere. Because the atmosphere is warming, it can hold more moisture, so precipitation can increase, but it can fall as snow only if cold enough, so broadly, some places across the U.S. are gaining snowfall.”

There is no evidence temperature changes have caused any ski areas to close or to have significantly impacted the length of the ski season as of yet, says Tonya Riley, director of marketing and communications for the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA). “Except for the 2019/20 season, which was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, ski season length has remained relatively consistent across all regions and ski areas of varying sizes over the past 20 years,” she explains. However, the amount of snow each season isn’t consistent. This prompts many owners and operators

of ski and snowboarding facilities to turn to snowmaking. “Approximately

87 percent of NSAA’s membership (260 resorts) leverage snowmaking to ensure a reliable, consistent experience and season opening,” Riley explains. “Seventeen percent of total skiable acres in the U.S. are covered by snowmaking.”

Snowmaking technology

Riley adds that, in total, approximately 79 percent of the Midwest region and 84.5 percent of the Southeast region are covered by snowmaking, a technology which forces water and pressurized air through a device to produce artificial snow. It’s this technology many resorts today depend on to open and stay operating through to the end of the traditional season, explains Nick Sargent, president of Snowsports Industries American. “Technology around snowmaking has become a big element of how resorts are able to open and stay open and produce a quality experience,” he says. “More of the larger and well-known resorts are looking for advancements in snowmaking to be able to blow more snow faster and blow snow in warmer temperatures so you’re not waiting for the freezing line.”

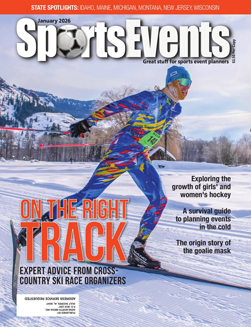

Photo courtesy Tamara Susa

Aspen, Colo., is one of the winter destinations impacted by rising temperatures, says Hannah Berman, sustainability and philanthropy senior manager for Aspen One. “In Aspen, we’ve lost a month of winter since 1980,” she explains. “That’s 31 days

that no longer get below freezing. Many resorts are increasing snowmaking. It’s become more efficient over the years, and we see it as a necessary evil to stay in business forever.”

Beaver Creek, Colo., is another sought-after destination for all things winter sports, and the mountain resort also turns to snowmaking systems to ensure there’s the needed terrain all season long. “These new, more efficient snowmaking systems not only contribute to our energy efficiency goals but also let us take advantage of favorable conditions for snowmaking whenever they arise thanks to automation in the systems,” says Eric Dunn, communications manager for Beaver Creek. “Our snowmaking systems have the ability to turn on when wet bulb temperatures hit or drop below 28 degrees, allowing our teams to create snow.”

In making snow, Beaver Creek is also focused on sustainability, as Dunn adds that most of the water it uses for snowmaking is non-consumptive, returning to the local watershed via snowmelt and is then available for immediate use. “We also monitor our water withdrawal to ensure that we do not exceed our water rights,” he says.

Photo courtesy Eric Dunn

Beyond snowmaking, many ski areas are going to great lengths to adapt to warming temperatures and ensure resiliency, Riley notes. Some of the most common practices being used include improving storm drainage systems to accommodate extreme rain events, participating in wildfire risk reduction measures and forest management practices, investing in higher efficiency and higher performing snowmaking operations, coupled with smart grooming and snow management best practices, modernizing avalanche mitigation efforts, investing in water rights, water facilities, enhanced storage, efficiency, and reuse projects and pre-forming slopes and terrain and managing vegetation to minimize the amount of snow needed, Riley adds.

“Sustainability is good business,” she says. “Ski areas continually invest in the long-term maintenance and elevation of the guest experience, including projects that reduce emissions and resource usage. Ski areas are working to mitigate their impacts, advocating for broad-scale climate solutions, and implementing strategies to boost their resilience in the face of a changing climate.”